data.plot()

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='Name'>

Weeks 12 and 13 are about using external scientific and engineering libraries that are not inside core Python, but are popular enough that we should learn them too.

Pandas is a Python library for easy and efficient numerical computation of table-like data. You can install it via either pip or conda with, for example the following command:

pip install pandas

We generally import pandas as "pd".

import pandas as pd

Assume that you have the following data:

columns = ['Name', 'Grade', 'Age']

data = [

['Jack', 40.2, 20],

['Amanda', 30.0, 25],

['Mary', 60.2, 19],

['John', 85.0, 30],

['Susan', 70.0, 28],

['Bill', 58.0, 28],

['Jill', 90.0, 27],

['Tom', 90.0, 24],

['Jerry', 72.0, 26],

['George', 79.0, 22],

['Elaine', 82.0, 23]

]

We can read this using pandas by converting it to a pandas.DataFrame:

data = pd.DataFrame(data=data, columns=columns)

Here's how it looks:

data

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Jack | 40.2 | 20 |

| 1 | Amanda | 30.0 | 25 |

| 2 | Mary | 60.2 | 19 |

| 3 | John | 85.0 | 30 |

| 4 | Susan | 70.0 | 28 |

| 5 | Bill | 58.0 | 28 |

| 6 | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| 7 | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

| 8 | Jerry | 72.0 | 26 |

| 9 | George | 79.0 | 22 |

| 10 | Elaine | 82.0 | 23 |

Pandas has a multitude of different reader and writer functions to read/write data from a different file format.

We can quickly save our data as a CSV file with .to_csv():

data.to_csv('my-data.csv', index=False)

And read it back using .read_csv():

data = pd.read_csv('my-data.csv')

Our data has three columns, and ten students. We can access a column like this:

data['Grade']

0 40.2 1 30.0 2 60.2 3 85.0 4 70.0 5 58.0 6 90.0 7 90.0 8 72.0 9 79.0 10 82.0 Name: Grade, dtype: float64

If we want, we can also create "horizontal columns" (i.e, an index), using the names of the students:

data.index = data['Name']

data

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | |||

| Jack | Jack | 40.2 | 20 |

| Amanda | Amanda | 30.0 | 25 |

| Mary | Mary | 60.2 | 19 |

| John | John | 85.0 | 30 |

| Susan | Susan | 70.0 | 28 |

| Bill | Bill | 58.0 | 28 |

| Jill | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| Tom | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

| Jerry | Jerry | 72.0 | 26 |

| George | George | 79.0 | 22 |

| Elaine | Elaine | 82.0 | 23 |

This way, we can access a student's information by providing their name as an index to the .loc[...] attribute:

data.loc['Amanda']

Name Amanda Grade 30.0 Age 25 Name: Amanda, dtype: object

If we didn't have an index, we could access a "row" using the .iloc[...] attribute with a numeric index:

data.iloc[1]

Name Amanda Grade 30.0 Age 25 Name: Amanda, dtype: object

data

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | |||

| Jack | Jack | 40.2 | 20 |

| Amanda | Amanda | 30.0 | 25 |

| Mary | Mary | 60.2 | 19 |

| John | John | 85.0 | 30 |

| Susan | Susan | 70.0 | 28 |

| Bill | Bill | 58.0 | 28 |

| Jill | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| Tom | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

| Jerry | Jerry | 72.0 | 26 |

| George | George | 79.0 | 22 |

| Elaine | Elaine | 82.0 | 23 |

We can access a specific grade, using the following syntax:

data.loc['Jack']['Grade']

40.2

data['Grade']['Jack']

40.2

data.loc['Jack', 'Grade']

40.2

One trick to watch out for: when we want to change a value inside of a DataFrame, you should use chained indexing.

If we try to change Jack's grade using this syntax, we get a warning:

data['Grade'].loc['Jack'] = 73

/Users/cagri/opt/anaconda3/lib/python3.8/site-packages/pandas/core/indexing.py:1637: SettingWithCopyWarning: A value is trying to be set on a copy of a slice from a DataFrame See the caveats in the documentation: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/user_guide/indexing.html#returning-a-view-versus-a-copy self._setitem_single_block(indexer, value, name)

Pandas will still update the value for you, but technically you're working on a copy of the data (as a result of the first indexing).

The best practice is to do this instead, which will not produce a warning:

data.loc['Jack', 'Grade'] = 83

data

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | |||

| Jack | Jack | 83.0 | 20 |

| Amanda | Amanda | 30.0 | 25 |

| Mary | Mary | 60.2 | 19 |

| John | John | 85.0 | 30 |

| Susan | Susan | 70.0 | 28 |

| Bill | Bill | 58.0 | 28 |

| Jill | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| Tom | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

| Jerry | Jerry | 72.0 | 26 |

| George | George | 79.0 | 22 |

| Elaine | Elaine | 82.0 | 23 |

Pandas has some nice functions that are useful for getting quick statistics about your data:

For numeric data, .describe() will produce some general stats about the given columns:

data.describe()

| Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|

| count | 11.000000 | 11.000000 |

| mean | 72.654545 | 24.727273 |

| std | 17.848045 | 3.495452 |

| min | 30.000000 | 19.000000 |

| 25% | 65.100000 | 22.500000 |

| 50% | 79.000000 | 25.000000 |

| 75% | 84.000000 | 27.500000 |

| max | 90.000000 | 30.000000 |

For example, we see that the mean age is 24.72.

.sort_values(col) will reorder the data such that the rows are sorted from lowest-to-highest for that given category:

data.sort_values('Grade')

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | |||

| Amanda | Amanda | 30.0 | 25 |

| Bill | Bill | 58.0 | 28 |

| Mary | Mary | 60.2 | 19 |

| Susan | Susan | 70.0 | 28 |

| Jerry | Jerry | 72.0 | 26 |

| George | George | 79.0 | 22 |

| Elaine | Elaine | 82.0 | 23 |

| Jack | Jack | 83.0 | 20 |

| John | John | 85.0 | 30 |

| Jill | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| Tom | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

Using ascending=False will sort the values from largest to smallest:

data.sort_values('Age', ascending=False)

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | |||

| John | John | 85.0 | 30 |

| Susan | Susan | 70.0 | 28 |

| Bill | Bill | 58.0 | 28 |

| Jill | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| Jerry | Jerry | 72.0 | 26 |

| Amanda | Amanda | 30.0 | 25 |

| Tom | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

| Elaine | Elaine | 82.0 | 23 |

| George | George | 79.0 | 22 |

| Jack | Jack | 83.0 | 20 |

| Mary | Mary | 60.2 | 19 |

.value_counts(col) can help with counting the number of different values for a given field:

data.value_counts('Grade')

Grade 90.0 2 30.0 1 58.0 1 60.2 1 70.0 1 72.0 1 79.0 1 82.0 1 83.0 1 85.0 1 dtype: int64

.nlargest(num, col) will give you the rows with the largest value for the given column:

data.nlargest(3, columns='Grade')

| Name | Grade | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | |||

| Jill | Jill | 90.0 | 27 |

| Tom | Tom | 90.0 | 24 |

| John | John | 85.0 | 30 |

Finally, .plot() will produce graphs of line plots of your data:

data.plot()

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='Name'>

data['Grade'].plot()

<AxesSubplot:xlabel='Name'>

As a final remark, if you ever wonder the internal datatype used to represent data in Pandas data, they are NumPy arrays:

data['Grade'].values

array([83. , 30. , 60.2, 85. , 70. , 58. , 90. , 90. , 72. , 79. , 82. ])

data.values

array([['Jack', 83.0, 20],

['Amanda', 30.0, 25],

['Mary', 60.2, 19],

['John', 85.0, 30],

['Susan', 70.0, 28],

['Bill', 58.0, 28],

['Jill', 90.0, 27],

['Tom', 90.0, 24],

['Jerry', 72.0, 26],

['George', 79.0, 22],

['Elaine', 82.0, 23]], dtype=object)

Matplotlib is a widely-used library to produce plots and graphs of various forms in Python.

You can install it via

pip install matplotlibimport matplotlib.pyplot as plt

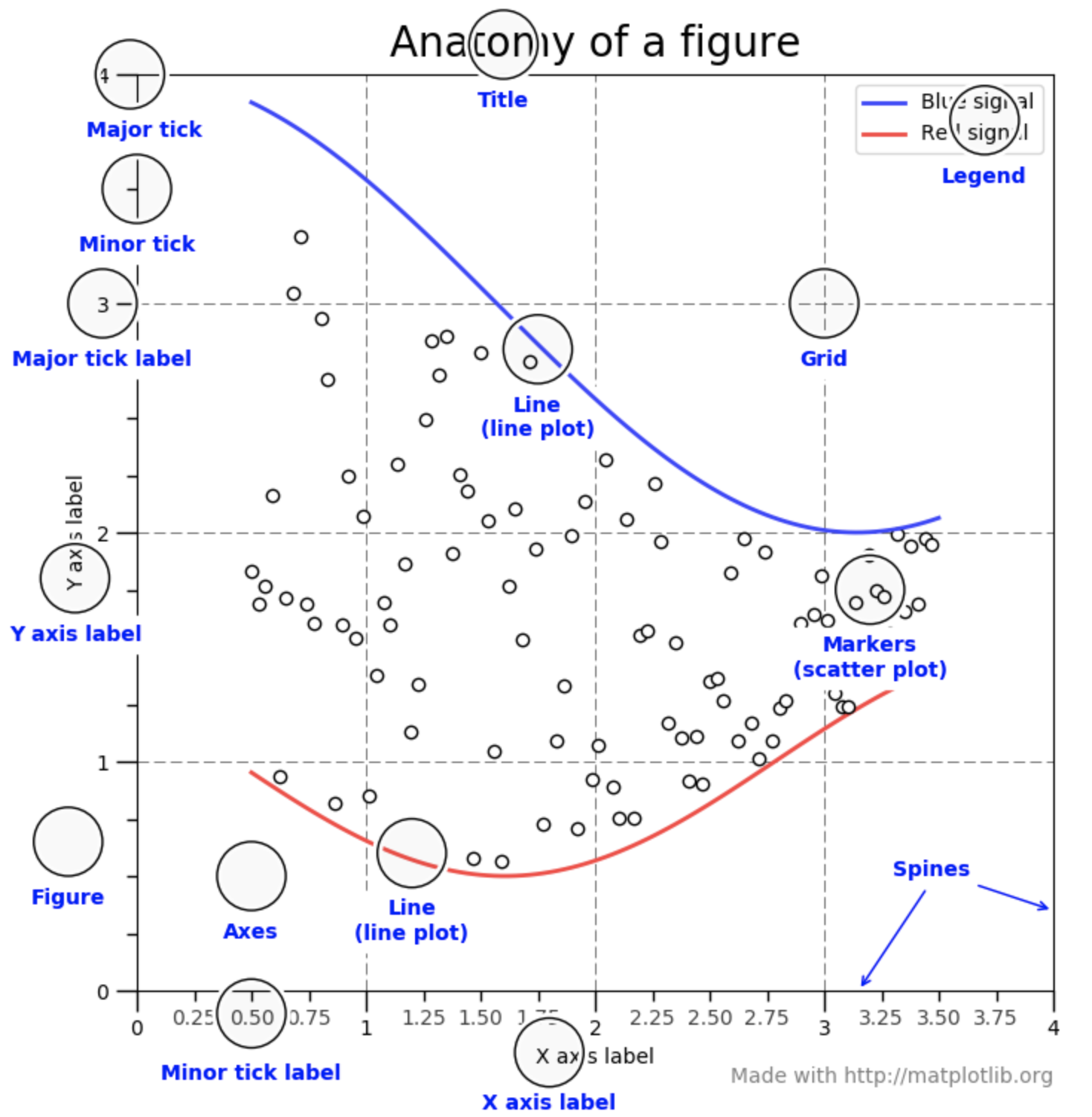

Let's go over the anatomy of a matplotlib graph, from the example in the textbook:

The figure above has several key features:

title), x-axis title (xtitle) and a y-axis title (ytitle). legend).ticks).Every part of the anatomical graph components are customizable in matplotlib.

Let's draw the simplest graph, using the pyplot API.

plt.plot(x_values, y_values) is for drawing a lineplot that passes through each pair of points given by x_values and y_values, which are either lists or NumPy arrays:

xs = list(range(10))

ys = [x**2 for x in xs]

plt.plot(xs, ys)

# Customizing the graph

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.title('Graph of x ** 2')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Graph of x ** 2')

If we need to plot multiple lines into the same plot, we can just call plt.plot() multiple times.

The following example makes use of the OOP approach of using matplotlib, which is calling plt.subplots() to get fig and ax objects, and using the ax object to draw the graph.

Notice that most function calls using ax are the same, but some have .set_ as a prefix to the function call.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot([x**2 for x in range(10)], label='$f(x) = x^2$')

# Display this with a gray color

ax.plot([x**3 for x in range(10)], label='$f(x) = x^3$', c='tab:gray')

ax.set_xlabel('x')

# Show 10 ticks

ax.set_xticks(range(10))

# Display the legend

ax.legend()

# Add a grid

ax.grid()

# Display the y values in logarithmic scale

ax.set_yscale('log')

ax.set_title('Graph of polynomials')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'Graph of polynomials')

We frequently need to draw multiple subplots inside a single plot, which is possible in the OOP style by giving row and column numbers to the plt.subplots() call to get multiple subplots, and then drawing each plot in its own plot:

# Plot x ** 2

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2) # 1 row, 2 columns of plots

ax[0].plot([x**2 for x in range(10)])

ax[0].set_xlabel('x')

ax[0].set_title('y = x ** 2')

# Plot x ** 3 on the second canvas

ax[1].plot([x**3 for x in range(10)])

ax[1].set_xlabel('x')

ax[1].set_title('y = x ** 3')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'y = x ** 3')

This is also possible using the pyplot style. To make plt switch to one specific subplot, the plt.subplot(...) call should end with the currently-switched plot number.

# Draw x ** 2

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1) # 1 row, 2 columns of plots, switch to first plot

plt.plot([x**2 for x in range(10)])

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.title('y = x ** 2')

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2) # Same thing, but switch to second plot

plt.plot([x**3 for x in range(10)])

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.title('y = x ** 3')

Text(0.5, 1.0, 'y = x ** 3')